Just four miles from Stony Brook University, at the intersection of Gun Path, Strong Neck Road, and Dyke Road, stands an unassuming sign reading the area “was Royal Residence of Setalcott Indians.” Its sheer insignificance, perched by the roadside, feels like an afterthought — a token acknowledgment that obscures the violent history of settlement. The sign’s past-tense language frames the Setalcott people as relics of another time, reducing them to a historical footnote rather than a living reality.

“The history of SBU [Stony Brook University] and really of Long Island, is not different from other American universities and the rest of the country, in that they often (almost always) occupy Indigenous land. We are not unique in this,” said SBU associate professor Joseph Pierce, a member of the Cherokee nation and leader of the University’s new Native American and Indigenous Studies (NAIS) Initiative.

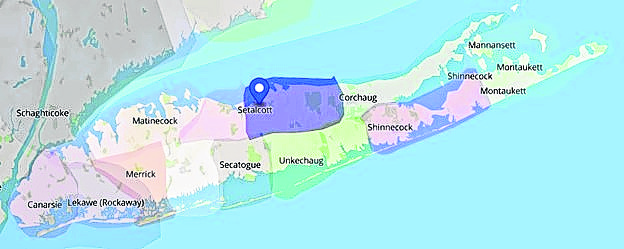

The Setalcott people call this area “Wopowog,” which means land at the narrows. As colonizers continued to encroach on their land, they displaced the tribe to other areas like Minasseroke, also known as Little Neck or Strong Neck.

Stony Brook University now occupies the region. Established in 1957, the university expanded rapidly, but it came at the cost of erasing indigenous history and presence in the area.

“We are a university that has not done much outreach over the years to Native peoples,” Pierce said. “We need to do much more and we need these issues to be a priority for the university as a whole.”

The only way to know the Setalcott people ever owned this land is squinting your eyes to read the tiny footer on the bottom of the SBU website, where land acknowledgment is.

“Stony Brook University resides on the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary lands of the aboriginal territory of the Setauket or the Setalcott tribe. We acknowledge federal and state-recognized tribes who live here now and those who were forcibly removed from their homelands. In offering this land acknowledgment, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty, history, and experience,” it reads.

Kevin Sells, an elder of the Setalcott Nation, said the land acknowledgment brings up painful memories of the past.

“In many cases, we were run off once our land got fenced or walled off. We’d set foot on what we considered our legitimate territory and were met with violence,” he said.

“The land acknowledgment is bitter to that heartburn, but it’s also somewhat comforting. It probably could’ve happened a long time ago. I know our elders and ancestors would’ve liked to see it.”

While the statement isn’t recent, discussions revolving around improvements to the acknowledgment recently came up alongside the University’s Native Studies initiative. Land acknowledgements generally began in the 1970s, becoming more common in the 2000s, because of a larger push for aboriginal peoples’ rights in Australia.

Land acknowledgments are also made at major university events. Before Interim President Richard McCormick made the annual State of the University address in September, an announcement played acknowledging that the university’s land was stripped from Indigenous tribes.

The university did not answer requests for comments.

Setalcott history

The Setalcott tribe occupied this land for centuries before the European settlers arrived in the 17th century. The tribe honored the land by fishing, hunting, and agriculture. They weaved their stories and spirituality into quits, passing down their history.

By the 1660s, settlers claimed around 35 acres of Setalcott land with a total disregard for Indigenous sovereignty or fair compensation. Fragmented land holdings and dwindling numbers eventually forced the Setalcott into marginal lands.

“We never really knew that we were selling the land. We had no concept of land ownership, only natural boundaries,” Sells said. “We believed we were making an agreement [with the colonists] in return for items and use of the land, which was common among tribes… our rights to use the land were completely abrogated.”

Eventually, the Setalcott tribe had been assimilated into colonial society or forced into a life of poverty.

“We didn’t have land, so we simply became part of the community. We stayed, we didn’t go anywhere, we just integrated,” Sells said. “But now we are being priced out of our historical and ancestral land. If we have land, we can stay.”

Without a reservation and federal recognition, the only remaining sign of their presence comes in the land acknowledgment and traditional ceremonies performed on other Long Island tribes’ land like the Setauket people.

For Pierce, these acknowledgments are not enough.

“A land acknowledgment is only ever a first step toward being in good relations with Native peoples,” Pierce said. “We still have a responsibility to engage with the people on whose land the University resides, to engage with them in an ethical and responsive way.”

Sells hopes the land acknowledgment and continued community engagement will lead to state recognition.

More recognition

Louisa B. Johnson, a faculty member at Stony Brook University, also shares this sentiment.

“We need to move beyond acknowledgment and into action that supports Indigenous communities,” Johnson said. “It’s not enough to just say we acknowledge the land; we must ensure our courses reflect the histories and contributions of Indigenous peoples,” she added.

Johnson and several other professors have begun integrating Indigenous perspectives into their syllabi, highlighting the significance of Indigenous knowledge and history.

“This is about making sure our students understand the full story of this land and its people,” Johnson said.

By emphasizing Indigenous voices in academia, these educators aim to create a more inclusive and comprehensive educational environment.

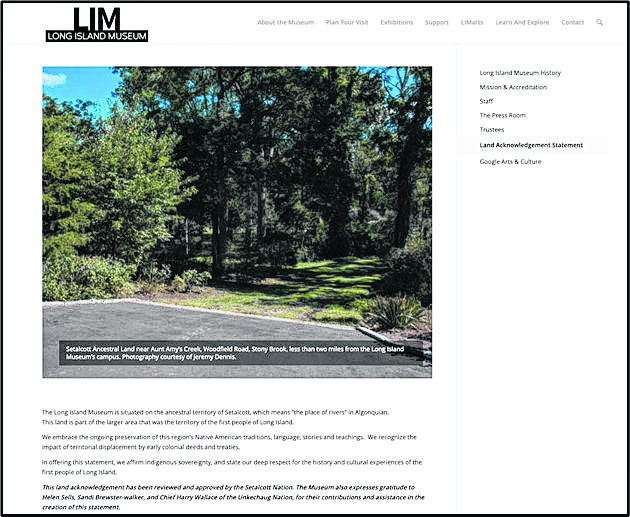

The Long Island Museum developed its own land acknowledgment through a collaborative process with Indigenous communities.

According to Joshua Ruff, the co-executive director at the Long Island Museum of American Art, History & Carriages, this initiative began in 2021 when the museum reached out to historian John Strong, who connected them with Montaukett Executive Director Sandi Brewster-Walker. The Montaukett people are another tribe on Long Island and recently saw Gov. Kathy Hochul veto a bill that would have granted them state recognition.

Sandi facilitated discussions with key figures in the Setalcott community, like Helen Sells and Carlton “Hub” Edwards, to ensure that the acknowledgment accurately reflects Indigenous history and recognizes their current presence.

This resulted in a statement which the Setalcott community approved in 2022. The statement prominently displayed both online and in its programming space. The museum also added works to their permanent collection by artists who have Indigenous heritage like Jeremy Dennis and Michael A. Butler.

“Very few people scroll to the bottom of a website,” Sells said. “[The University’s land acknowledgment] would be more respectful if it was in a more prominent place. It could be managed and presented better.”

More action called for

This collaborative approach to recognition highlights a model that proponents say Stony Brook University should aspire to replicate.

According to Pierce, the university’s land acknowledgment must be paired with concrete actions that foster genuine relationships with Indigenous communities like the NAIS Initiative.

The program will establish a minor in Native American and Indigenous Studies, offering courses on Native history, culture, and environmental justice.

“I would like to see members of the Setalcott Nation being allowed to take those courses without fee because we have youngsters that have very little idea of their history,” Sells said. “As our elders pass on, stories get shorter and they lose detail.”

Sells also added that this could enhance the learning experience of all students.

“It would be nice to be able to point and ask the Setalcott member, ‘what are your stories?’” he explained. “It might go a long way. Some of these old stories are not as accurate as they could be and if we have academics studying it and teaching it, our people would get more accurate information.”

Students will also be required to participate in community-oriented initiatives with local Indigenous groups.

“We have to continue to build relationships and grow our community, but it takes time and demonstrating that the University is capable of sustaining those relationships.

Up to now, it has not really shown that,” Pierce said.

The Setalcott community continues to advocate for recognition and the preservation of their heritage, even though they do not have an official reservation, by working with other Indigenous groups in the region. Institutions like Stony Brook University have a critical opportunity in supporting their initiatives.

“There is no part of the world that Indigenous people have not made significant contributions to,” Pierce said. “We have always been dynamic thinkers and participants in the world and will continue to be long into the future.”

Lori Saxena and Jenna Zaza are reporters with The SBU Media Group, part of Stony Brook University’s School of Communication and Journalism’s Working Newsroom program for students and local media.

Read also: MLK’s Great Neck visits strengthen civil rights mission