One hundred and eighty-five years ago this week, during one of the coldest winters on record, a man named David Crowley washed ashore at Baiting Hollow in Riverhead after drifting for 48 hours on a bale of cotton, following a spectacular steamboat fire in Long Island Sound — and capping one of the most harrowing survival odysseys in North Fork history.

Fearful of drowning after two days and nights at sea, his hands and feet frozen into “marble,” Mr. Crowley crawled across ice sheets to shore and scaled a massive mound of snow that had formed on the beach. From there, it is believed, he climbed a steep slope in the dark and stumbled nearly a mile to a cottage with a light on.

The 25-year-old was one of only four who had survived the sinking of the steamboat Lexington after a fire burned the 205-foot wooden paddlewheel steamer on Jan. 13, 1840, killing as many as 149 people on board. The catastrophe, which remains the worst maritime disaster in Long Island Sound history, was the subject of an incisive lecture last weekend at the Suffolk County Historical Society in Riverhead by Bill Bleyer, author of “The Sinking of the Lexington on Long Island Sound.”

“It was sort of the Titanic of its age,” Mr. Bleyer, a Long Island maritime expert and retired Newsday journalist, told the gathered audience.

Early January 1840 was bitterly cold in New York. The East River was “frozen almost solid,” Mr. Bleyer said. “The ice is all the way out into the Long Island Sound.”

The Lexington wasn’t even supposed to run that day, but it was the only steamboat believed capable of reaching its Stonington, Conn., destination from New York City in those conditions.

Among the passengers on that ill-fated voyage was Charley Foley, a Harvard professor and architect, returning to New England for the dedication of a church he had designed in Lexington. There was a pair of famous comics, Charles Eberle and Henry Finn, who Mr. Bleyer called the “Abbott & Costello of their time.” Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had also booked passage on the trip, but decided to remain in New York City that day. The cargo included $50,000 in gold and silver coins and 150 300-pound bales of compressed cotton.

Around 7:30 p.m., several hours into the trip, the Lexington was four miles north of Eaton’s Neck in Huntington Bay, cruising at 13 miles an hour, when a crewman alerted ship pilot Stephen Manchester to a fire breaking out around the smokestack.

Captain George Child and Chester Hillard, a ship captain traveling that day as a passenger, raced to the pilot house.

“Their first gut reaction is: ‘This is a wooden steamboat covered in varnish and paint — it’s a fire trap,’ ” Mr. Bleyer said.

Cotton bales began catching fire on the steamboat. The hose on a portable water pump burned up.

“From there, things start to go wrong very quickly,” he continued.

First, the steering wheel snapped, after a series of rawhide ropes connecting the wheel to the rudder burned. There was an emergency tiller — a backup steering mechanism that would allow the crew to manually control the boat’s rudder — but the fire spreading in both directions from the middle of the ship made it unreachable.

Flames forced the crew from the engine room, so they couldn’t release the steam pressure, and the boat careened further out into the Sound for another 15 to 20 minutes.

The Lexington’s three lifeboats were deployed, but quickly capsized or drifted off, sending passengers to an icy death in the 10-degree water. (Only after the 1912 Titanic disaster did maritime rules require a lifeboat seat for every person on board, Mr. Bleyer noted.)

By 8 p.m., crew members began sending people overboard on cotton bales that were not already on fire — including Mr. Crowley, the second mate in charge of the bucket brigade.

“He’s dry but only wearing shirtsleeves, pants and a vest — no hat, no coat.”

Mr. Manchester and Mr. Hillard managed to ride the bales away from the fire-ravaged ship, while a third man — firefighter Charles Smith — floated off on a bale, slid off it into the icy waters, and then caught a piece of the boat’s broken paddle wheel. Everyone else on board that night perished.

Boat captains on Long Island and Connecticut could see the flames from shore but were stymied by low tide and ice-filled harbors.

By morning, Southport Captain Oliver Meeker and his crew, who had earlier run aground trying to get the sloop Merchant out of the harbor, made it into the Sound. One by one that afternoon, Hilliard, Manchester and Smith were rescued while Crowley, drifting further to the east, looked on helplessly.

“He puts a handkerchief in his frozen hands — trying, yelling, waving — trying to get the attention of somebody on … the boat, but they don’t see him, and leave and go back to Southport,” Mr. Bleyer said.

With no food or water, Crowley had been drifting for about 15 hours when he grabbed a branch floating by and tried to use it as a paddle to reach the Connecticut shore.

“He gets very close, then the tide and the wind change, and take him back out to the middle of the Sound on the Connecticut side. A little bit later, he’s drifting towards Falkner Island … he tries to get to shore there, but the tide again changes and takes him east,” Mr Bleyer recounted.

Mr. Crowley drifted nearly 50 miles over about 48 hours before washing up on the east end of Baiting Hollow, somewhere between what is now Park Road and Roanoke Avenue, according to North Fork historian Richard Wines.

The area where David Crowley came ashore is seen on this 1850 map of what is now Sound Avenue between Park Road and Roanoke Ave. (Courtesy photo)

The cliffs along the Sound shoreline are about 150 feet high, Mr. Wines said in an email, citing a U.S. Geological Survey. All the homes at the time were about three-quarters of a mile south of the shore, where Sound Avenue is today.

Mr. Wines said all the woodland in the area had been clear-cut to provide cordwood for the New York City market, so that Mr. Crowley likely climbed to the top of the cliff and saw a light in a house down along what’s now Sound Avenue.

An elderly couple, Matthias and Mary Hutchinson, were up late after a rare visit from their son.

“Otherwise they would not have heard that knock on the door,” Mr. Bleyer said.

The veteran journalist quoted from a description of that night that Mary Hutchinson gave to her grandson, who wrote a book about the family history.

“There was a feeble knock at the kitchen door followed by a faint cry of distress,” she recalled. “On opening the door, we discovered the prostrate figure of a young man, about 25 years of age, of sturdy proportions, without coat or hat … and then we saw that his hands and arms resembled marble. They were solidly frozen, as his feet proved to be once we cut off his boots. We immediately removed him to a cold room, and immersed his extremities in cold water.”

Mr. Bleyer said that thanks to the couple’s quick thinking, according to one report, Mr. Crowley lost only a toe and a half.

“If you warm up somebody’s frostbitten flesh quickly, it dies. It turns gangrene and will kill you if it’s not amputated. They knew to warm him up very carefully, very slowly overnight, and saved him from a much worse fate.”

By morning, after a “few spoonfuls of beef tea,” Mr. Crowley recounted his nightmare to the astonished couple.

Mary Hutchinson told her grandson that “the first request that Mr. Crowley made the next day was that the bale of cotton be secured, as a souvenir of the imminent perils for which he had passed. This was done.”

For nine months, Mr. Crowley remained with the Hutchinsons, recovering.

“When he goes home, he takes the cotton bale with him,” Mr. Bleyer said. “Has it in his living room, where he’s living with his mother, who is so horrified at the whole experience and this daily reminder of what he went through that she insists he hide it in a closet, which he does.”

Mr. Crowley kept the bale of cotton for more than two decades, ultimately selling it for more than $400 during the Civil War, when it was used to make uniforms for Union soldiers. He continued working for the steamboat industry for 53 years, before his retiring in 1893.

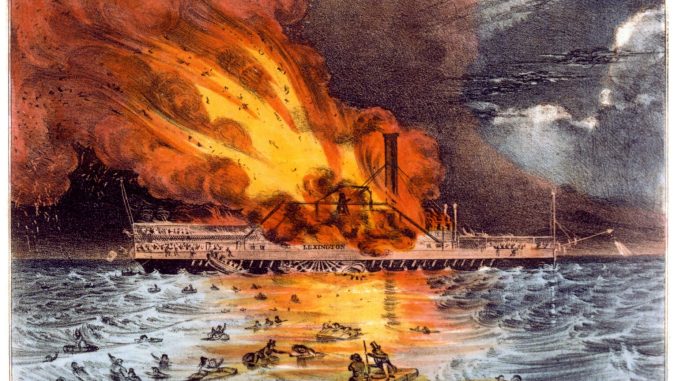

The wreck of the Lexington was a blockbuster story for the media, and launched the career of Manhattan lithographer Nathaniel Currier, of the famed printing firm Currier & Ives. Lithography is a printing technique that uses a flat stone or metal plate to create images.

Since daily newspaper illustrations were limited to what you could carve into a block of wood, the New York Sun, one of the nation’s largest papers at the time, hired Mr. Currier to make a lithograph of the burning steamboat. He and his team of artists worked around the clock.

Remarkably, Mr. Currier’s team used colored pencils and crayons to individually illustrate each newspaper copy’s black and white image of the raging fire on the steamboat.

“Currier had a staff of young, single women working in his office. They would take the black and white version, and pass it down from woman to woman. Each one had a different colored pencil, and each added one color and then passed it down to the next person,” Mr. Bleyer said. “When all the colors are in, they would take it back to the Sun to sell.”

Over the course of three weeks, the Currier team colorized, and the Sun sold, more than 20,000 copies, Mr. Bleyer said.

“The Sinking of the Lexington on Long Island Sound” is available in local bookstores across Long Island.