Steve Wick, local author and journalist, will host a book release for his title “All That Remains” at Cutchogue New Suffolk Library on Saturday, Oct. 26, at 2 p.m. The book chronicles the lives of the last residents of the Depot Lane migrant camp in the years leading up to the May 2006 fire that destroyed a barn on the property and led to the camp’s closure.

Mr. Wick spoke with The Suffolk Times on his efforts to document the last migrant camp on Long Island.

How did you learn about the camp?

One day I saw a painfully thin Black man coming out of King Kullen on a bike and I wondered where he was going. I followed him up Depot Lane, and I saw him go into this camp building around the barn, this low, cinder block building where they were living. And I thought, “Gee, I didn’t know anybody lived there.” And then the next day, I went back and knocked on the door and met the people. And over the course of the next two or three years, the photographer [Viorel Florescu] and I just walked in and out, meeting everyone.

I knew it was the last camp of its kind out here. There used to be dozens of farm labor camps in which Black men and women, and even some children, lived. As the potato industry disappeared, this became the last camp.

Who were these residents, and how did they come to live there?

They would start in Florida with strawberries or oranges, depending on the seasons, and in the fall they would end up on eastern Long Island doing potatoes. There were these Black labor camps on the South Fork and the North Fork and all over. But I think for the last 15 years at the Depot Lane camp, they stayed there full-time. They just lived there, and they would find work during the off seasons. But they weren’t migratory at that point. All of them had done migratory work up and down the East Coast, and as the farms here shrank away, the potato farms, they ended up just staying.

What made you want to tell their story?

I think the story that I really wanted to write is, well, what happens to these people now? This is all they’ve ever known. This is the life they’ve had since they were children, coming up and down the coast, living in camps. And now there’s no more. There’s no more potato grading. The barn was gone, and the camp got shuttered … So for me, there was just a world of great stories to be told, and a kind of historic story to be told, really about the last of these people here.

It honors the people who live in that camp, who otherwise were kind of ignored. A lot of these Black camps were just kind of left on their own. And then as the farming industry changed and they closed, these people were just kind of left to their own wits … So this history will be preserved, and their stories will be told.

Who were some of the people you encountered?

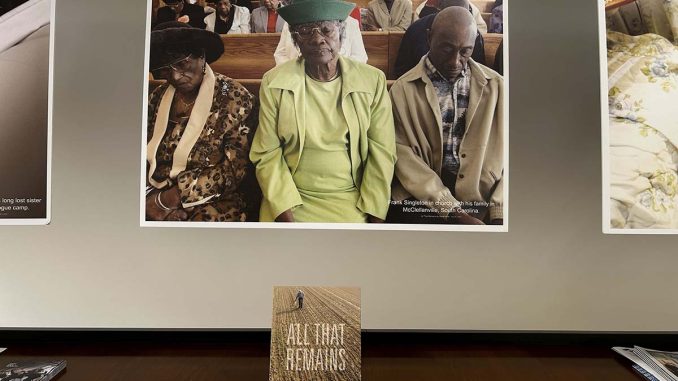

Frank. He wasn’t sure what his name was, he’d lived there so for so long, and it took a long time to find his family in South Carolina, but we eventually found that he had a mother and a brother and a couple of sisters in very rural South Carolina, and he wanted to go home. He had no identification, no money. The only clothes he had were clothes in a plastic bag. And the photographer and I picked him up on Saturday night, and drove him all the way to South Carolina. He’d been gone for 35 years or so.

Oliver Burke. One of the first days I was reporting in there, he asked me to see if I could find his birth certificate. And while I never found his birth certificate, I did find that where he was born. I ended up finding his mother, and when I talked to her, she said she gave up her son when he was a baby to another couple she knew. [They were going north] to pick blueberries in New Jersey. And this boy then grew up in these camps. He ended up in this camp on Depot Lane, and he wanted to go home, and he had an ID so he could actually fly. We went with him on the plane and took him home with his mother, who we hadn’t seen since he was a baby.

Jimmy Wilson. The oldest guy there, Jimmy Wilson, was born in 1918 and he left rural Georgia as a five-year-old because there was so much violence against Blacks. There were so many lynchings. And he went into Florida with his grandmother, where there were even more lynchings. And he ended up getting on a truck going north as a 14-year-old, picking potatoes in New Jersey and ending up out on Long Island, and he never went back. And I asked him 100 times, I said, “Jimmy, there’s nothing here. The place burned down. What are you going to do? I’ll be glad to drive you to rural Georgia,” and he said to me emphatically, “I will never, ever go back to rural Georgia.” His experience there was so bad.

What makes this story significant?

To me, there was something incredibly American about those people. They represent a history of the North Fork and eastern Long Island that has gone ignored for too long. We wrote about the farmers’ history. Who wrote about the workers? Who wrote about these Black men and women? This book is an effort to save a unique part of the history of this place. But beyond that, this is also the story of America … So, to me, that camp encompasses a lot of local history that’s been ignored and a lot of American history that we really haven’t dealt with in an upfront way.