The Town of Riverhead on Wednesday filed a complaint in county court against Southampton Town in an effort to force Southampton to rethink its planned creation of a massive, high-density development project in the hamlet of Riverside, one of Suffolk’s poorest communities, which sits on the edge of downtown Riverhead but is in Southampton.

It’s the latest salvo in an increasingly bitter dispute between the neighboring towns over the planned development — and its new sewer district — which Riverhead officials fear will overwhelm years of planning and new development in downtown Riverhead and overburden the town’s school district, which serves the Riverside community.

“All of the negative social and environmental impacts associated with intensive future development of Riverside will be exported into Riverhead far more than into the balance of Southampton,” Riverhead’s complaint alleges. “Put simply and colloquially, when Riverside sneezes, Riverhead catches the cold.”

For months, the two towns have been at odds over the plan — to the point where, in May, Suffolk County Executive Ed Romaine brokered a meeting between Riverhead Supervisor Tim Hubbard and Southampton Supervisor Maria Moore to try and mitigate the disputes, with little success, according to officials from both towns. When Riverhead signaled its intent earlier this year to sue Southampton, communications between the two towns broke down.

Mr. Hubbard and other town officials have repeatedly petitioned Southampton officials at public meetings and in written correspondence to reconsider the plan, which could see the creation of more than a thousand new housing units, many aimed at low-income families, and a fresh influx of new students to the already over capacity Riverhead Central School District.

The original Riverside Revitalization Action Plan, forged nearly a decade ago, called for up to 3.2 million square feet of new, mixed-used development in Riverside that could include as many as 2300 new low-income housing units. The latter figure has been reduced to 1167 housing units overall, according to interviews with Riverhead and Southampton officials — though it remains unclear how many of those units would be high-density, affordable housing.

The 1167 figure “is something that we’re reviewing again, now, because I don’t think the [Town] Board is comfortable even with that number,” Ms. Moore said in an interview earlier this week. “We want to have smart growth. We don’t want to just overwhelm a community.”

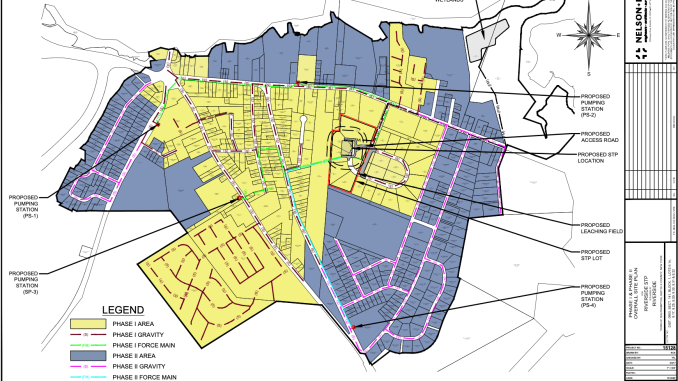

The complaint — the first step in a lawsuit — seeks to “annul and vacate” the supplemental final generic environmental impact statement that Southampton approved earlier this year, which paved the way for a new Riverside sewer district with the capacity to treat 400,000 gallons of wastewater a day.

Riverhead officials charge that Southampton failed to include in the new sewer district the Suffolk County Center, which is also in Southampton but since the late 1960s has been serviced for a fee by Riverhead’s sewer district. For years, the two towns have been tangled up in litigation over the fees Riverhead charges Southampton for that service, with Southampton withholding a portion of the fees in recent years, according to Riverhead officials.

Riverhead also wants Southampton to include the Phillips Ave. Elementary School — which generates about 6,000 gallons of wastewater a day — within its planned sewer district. Plans for the project say the sewer plant would be built on land immediately adjacent to the school, as close as 500 feet, though Ms. Moore said earlier this week that planners are now considering moving the plant further from the school.

Mr. Hubbard said in a press release on Thursday that Riverhead was “forced to bring this action” to “make sure that the Riverside revitalization and sewage treatment plan was the best that it could be and to protect the hard work it has done to effectuate meaningful revitalization in Downtown Riverhead.”

He said the current plan “does not take into account any of the dramatic demographic changes the area has experienced in the last 10 years or the revitalization plans of Riverhead.”

Mr. Hubbard said in the statement that placing the new sewage treatment plant right next to the elementary school but failing to include the school in the new sewer district “was the ultimate slap in the face to the families and teachers there.”

Since the Riverhead sewer district is required to reserve a 200,000 gallons-a-day capacity for the county center’s wastewater, Riverhead officials say their district is now operating at capacity and cannot serve the needs created by the significant new development in downtown Riverhead in recent years.

Riverhead’s sewer district has a capacity to treat 1.2 million gallons of wastewater daily, according to the town website, and is currently treating about 900,000 gallons a day.

Southampton has agreed to include the county center in the Riverside sewer district, but only in a future phase of the development plan. Southampton officials claim they have offered more than once, without success, to take over the county center’s sewage treatment.

“There were offers made under prior administrations to Riverhead to take over the county center … and Riverhead declined that offer,” Ms. Moore told the Riverhead News-Review.

“Now, at the 11th hour, so to speak, Riverhead is back, saying ‘well, now we do want you to take it over, because we need more flow, because we have own plans to revitalize our own downtown.’ We’ll look at that for phase two. We’re only building phase one now, but we were on a very tight deadline to finalize the documents” to secure a significant amount of grant money.

“It takes a lot of years to put the planning in place and acquire all the properties that are needed and get the grant funding,” she said. “Over the course of that time, if Riverhead had changed its mind, I believe it would have been incumbent upon them to come back to us — and not in the year that we’re ready to finalize our funding.”

Riverhead officials counter that any earlier offers to previous officials were informal, verbal conversations, with nothing documented in writing. Earlier this year, Ms. Moore — a former mayor of Westhampton Beach — succeeded previous Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman, who served six years.

Ms. Moore said the plan has been in the works for nearly a decade.

“I really think it’s a waste of taxpayer money and resources to start this lawsuit,” she said earlier this week. “I feel confident that we’ll prevail, because we haven’t done anything wrong. We’ve followed all of the procedures that are required, and the plan is a good one.”

Dawn Thomas, Riverhead’s Community Development Agency administrator, said in an interview this week that had Southampton “done stakeholder engagement in this project, which they ought to have done because [the plan] was 10 years old, we could have avoided all of this.

“So, what they can do and what their lawyers told them to do is great, but the practical reality is that what you can do and what you should do are often two very different things. The failure to engage the community in this giant project is a failure of planning. That’s not how planning is supposed to work.”

Pressed on Riverhead’s claim that Southampton’s current environmental impact statement is insufficient and incomplete, Ms. Moore said that “we operated with the guidance of our town attorneys, and they’ve assured us that we followed all the procedures properly.”

Riverhead’s complaints are animated by the sense that a much wealthier town is running roughshod over the needs of a far poorer town, officials said.

Across the five East End towns, the Community Preservation Fund real estate tax has generated more than $2 billion since its inception in 1999, though 85% of that revenue was generated in Southampton and East Hampton.

New figures released recently by the office of Assemblyman Fred Thiele, one of the architects of the original legislation, estimated that Southampton took in about $41 million in CPF funds in the first half of 2024, compared with East Hampton’s $25 million, Southold’s $5.75 million, Riverhead’s $4.6 million and Shelter Island’s $1 million.

Since 1999, the CPF tax has generated about $92.4 million for Riverhead and more than $1.2 billion for Southampton.

Both Riverside and Riverhead are federally designated as Areas of Persistent Poverty, Environmental Justice Areas and are considered Historically Disadvantaged.

Riverhead officials also contend in the complaint that by concentrating so much affordable housing in one already highly segregated community, Southampton is promulgating what two officials described in separate interviews as “inverse redlining.”

“The Riverside neighborhood is the lowest income area in Southampton, and has highest concentration of racial and ethnic minorities,” the complaint contends, arguing that since the Riverside development plan was adopted in 2015, “Riverside’s resident population has become almost entirely Hispanic and is one of the poorest communities … in Suffolk County.”

Ms. Moore said in the interview that she was “left speechless” over that allegation.

“They’re assuming that the people who avail themselves of workforce housing are going to be of certain ethnicities, and that’s not necessarily the case,” she said.

According to state data, for the 2022-2023 school year, the Riverhead Central School District was 63% Hispanic, 26% white, 8% Black, 2% multi-racial and 1% Asian.

Caught in the middle of the dispute is the school district, which declined to participate in Riverhead Town’s lawsuit against Southampton.

Riverhead Central School District President James Scudder told the News-Review in an email this week that “we have no interest in getting involved in any litigation.

“We have voiced our concerns about the [planned Riverside sewer treatment plant] to the Town of Southampton — about its location and proximity to Phillips Elementary. We have also voiced concern about the increased enrollment that the development plan will have on the school district. We hope that the Southampton Town Board will take those concerns into consideration as they continue their revitalization plan. We only asked that they keep the lines of communication open and listen to our concerns.”

A former Riverhead school district official, who requested anonymity to speak frankly about a controversial issue, described the district as a child caught between two divorcing parents. The former official pointed out that two school expansion bond issues have been voted down in Riverhead in recent years.

“We need more room at Phillips [elementary school], we need more room at the middle school and more room at the high school. Southampton has at least expressed an interest in helping with that. Riverhead has flatly denied it.”

The former official was referring to more than $2 million a year in Southampton Town CPF funds that the Southampton pays to the Riverhead school district annually to compensate for the removal of the preserved parcels in Riverside from the school district’s tax rolls.

“We might be one of the only towns that do it right,” Ms. Moore said of the practice. “Any properties that come off the tax rolls, either because of us or even county acquisitions, we compensate the school districts.”

She declined to say whether additional funding would be allocated for the Riverhead school district, above the current annual rate.

The Riverside development plan is being financed, according to the Southampton Press, with a $19.24 million New York State Environmental Facilities Corporation Clean Water State Revolving Fund grant; a $10.9 million Community Preservation Fund Water Quality Improvement Project grant; a $5 million grant from the Suffolk County Federal Infrastructure Funding; a $5 million federal grant from the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023; $3.3 million of Community Preservation Fund Water Quality Improvement Project money for land acquisition; $904,500 in CPF money for connection fees; and a $250,000 grant from the Suffolk County Water Quality Protection and Restoration Program. Ms. Moore’s office did not immediately respond to a request to confirm the financing figures.