Everyone agrees that American students need better civics education.

Civic knowledge in America is abysmal. Fewer than half of American adults can name the three branches of government—and a quarter can’t name any branch at all.

Likewise, a quarter of Americans couldn’t name any of the five freedoms guaranteed under the First Amendment.

That’s why supporters of civics education might be inclined to celebrate the recent announcement that a private initiative called Educating for American Democracy would award $600,000 in grants for K–5 pilot implementation projects to applicants from California, Georgia, Missouri, New York, and Wisconsin.

But for supporters of true civics education, popping the champagne in this case would be a grave mistake.

“EAD is a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” warns Mark Bauerlein, a professor emeritus at Emory University. In his telling, the seemingly innocuous goals of Educating for American Democracy, such as inculcating an “inquisitive mindset towards civics and history,” mask a more radical agenda. As Bauerlein explains:

Yes, [Educating for American Democracy] contains a few traditionalist elements that deflect the charge of anti-conservatism. Overall, however, the EAD Roadmap circumscribes those elements with identity politics that left-wing teachers can plunder all year long. Here is what EAD really means by “inquisitive mindset”: a takedown of heroes, emphasis on victims (women and racial minorities), denial of American exceptionalism, and a focus on the failings of the founding.

According to David Randall, director of research at the National Association of Scholars, Educating for American Democracy is among the worst civics education resources.

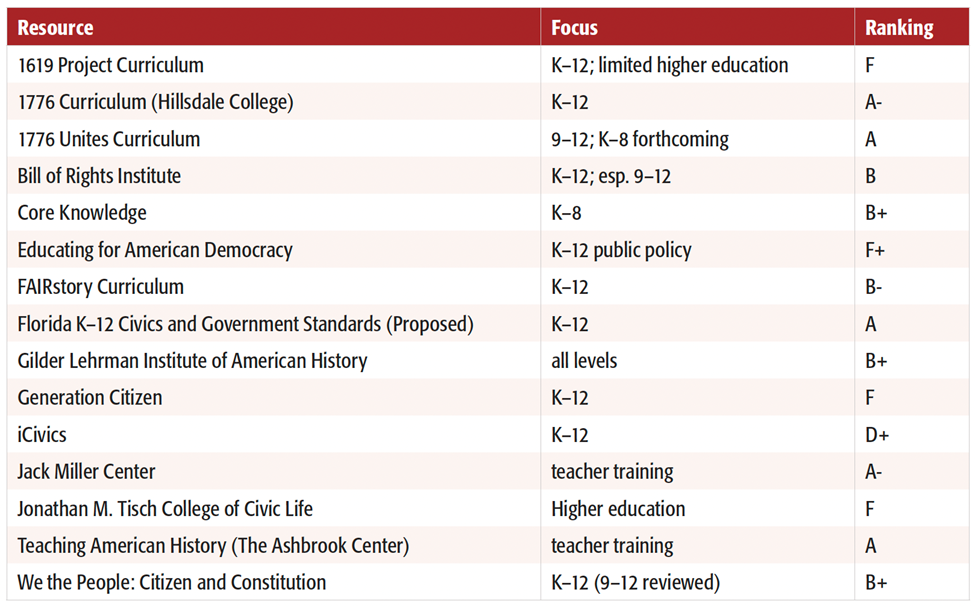

In a 2022 report by the Pioneer Institute and the National Association of Scholars, “Learning for Self-Government: A K-12 Civics Report Card,” Randall gave the EAD an “F+” on a scale of A through F. (See chart below.)

Why the poor grade? Randall said EAD is “the central political-administrative push to reshape American civics education into a radical mold,” with the goal “to get every state civics education standard aligned for action civics and abbreviating as much as possible traditional civics education.”

What is “action civics”? According to the Pedagogy Companion to the Roadmap to Educating for American Democracy, it is “a specialized form of project-based learning that emphasizes youth voice and expertise based on their own capabilities and experience, learning by direct engagement with a democratic system and institutions, and reflection on impact.”

If you’re still confused, that’s because, as Randall observes, the proponents of action civics and other radical pedagogies use “impenetrable, jargon-heavy terms” to mask their true agenda.

In his report, Randall explains what action civics really entails:

What this means is that in ‘action civics’ history and government classes, students spend class time and receive class credit for work with ‘nongovernmental community organizations.’ This substitution degrades teachers’ and students’ esteem for classroom instruction, which is deemed not to have sufficient civic purpose in itself. It reduces the scarce time available for students actually to learn about the history of their country and the nature of their republic.

Most importantly, it introduces a pedagogy that facilitates teachers’ ability to impose their personal predilections on their students, by influencing the process by which students choose ‘community partners’ with which to work. It also facilitates the ability of peer pressure to impose group predilections on individual, dissenting students. We may note that the advocates of ‘action civics’ explicitly distinguish this activity from volunteering: action civics is meant to change the political system, not to support civil society.

In other words, Randall explains, in place of real civics, action civics “substitutes radical progressive pedagogy as a vocational training for activism.”

In action civics courses, students get class credit for attending protests or supporting progressive organizations. The EAD website’s “Educator Resources” includes links to resources from left-wing organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center, whose “Learning for Justice” curriculum provides lessons on the “concepts of intersectionality, privilege and oppression.”

Instead of inculcating students with a Madisonian appreciation for our constitutional order, EAD-backed action civics programs train Alinskyite activists.

It’s easy to see why the Democrat-controlled Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and public school districts in Los Angeles and New York are excited to accept EAD funds. What’s harder to understand is why the Georgia Department of Education would be.

Georgia’s superintendent of schools, Richard Woods, is a Republican who previously wrote that the “ideology of Critical Race Theory (CRT) has no place in our schools and classrooms” and cautioned that “[w]e must be vigilant against embracing polarizing practices that only seek to divide us.”

Vigilance against embracing radical and polarizing practices in education is certainly necessary. Georgia policymakers should start by exercising greater vigilance over the grants they accept to further civics education.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email, letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.