No one can ever accuse Roger Deakins of having lived a dull life. The storied cinematographer has been nominated for 16 Academy Awards, winning twice for Blade Runner 2049 (2017) and 1917 (2019). He’s been a go-to for the Coen brothers a dozen times dating back to his first project with them (1991’s Barton Fink) and has also worked with a number of other renowned directors including Sam Mendes (Jarhead, 1917), Martin Scorsese (Kundun), Norman Jewison (The Hurricane), John Sayles (Passionfish) and Ron Howard (A Beautiful Mind).

(CC BY 2.0)

And while he’s been collaborating with his spouse Isabella James Purefoy Ellis the past three-plus decades ever since the couple met on a movie set back in 1992, the cinematic duo launched a podcast called Team Deakins back in 2020 and also released Byways, a collection of photographic stills that have also been exhibited in a number of art spaces and galleries across the United States and in Europe.

It’s been quite a heady road for a young lad who was born in the sleepy English seaside town of Devon. As Deakins recalled, there wasn’t much to do growing up aside from heading off to art college to avoid a 9-to-5 grind and becoming a member of a local film society. And as a shutterbug and a cinematographer, he wound up becoming a late bloomer.

“I was probably 20 years old when I first started shooting still photography and I didn’t pick up a film camera until I went to the National Film School,” he said. “I was quite late into movies—I must have been 24 or 25 before I touched a film camera. It gradually crept up on me. I liked photography. I liked looking at books of photography when I was a kid. I joined a film society. I grew up in a seaside town in Devon—there wasn’t much to do. I joined a film club. I saw some amazing movies, which I remember clearly like Peter Watkins’ The War Game. You’ve got to think that this was 1965 at the height of the Cold War. It was about what would happen if a bomb was dropped in the center of London. It was an amazing docudrama. I think it won an Academy Award for the Best Documentary. [Ed. Note: It won for Best Documentary Feature in 1967]. It was made for the BBC and it was banned for the next 25 years so nobody saw it. It was so shocking. It was shown in film societies prior to it being banned. I remember that and I remember seeing Alphaville very clearly. There were a few films like that—mainly European films. There were many film societies that were showing films that weren’t being shown in the cinemas.”

“I was probably 20 years old when I first started shooting still photography and I didn’t pick up a film camera until I went to the National Film School,” he said. “I was quite late into movies—I must have been 24 or 25 before I touched a film camera. It gradually crept up on me. I liked photography. I liked looking at books of photography when I was a kid. I joined a film society. I grew up in a seaside town in Devon—there wasn’t much to do. I joined a film club. I saw some amazing movies, which I remember clearly like Peter Watkins’ The War Game. You’ve got to think that this was 1965 at the height of the Cold War. It was about what would happen if a bomb was dropped in the center of London. It was an amazing docudrama. I think it won an Academy Award for the Best Documentary. [Ed. Note: It won for Best Documentary Feature in 1967]. It was made for the BBC and it was banned for the next 25 years so nobody saw it. It was so shocking. It was shown in film societies prior to it being banned. I remember that and I remember seeing Alphaville very clearly. There were a few films like that—mainly European films. There were many film societies that were showing films that weren’t being shown in the cinemas.”

As someone with an affinity for war movies and documentaries, Deakins’ earliest forays into filmmaking found him hired to head into war zones in Eritrea and what was-then Rhodesia in the ‘70s to shoot what became Eritrea-Behind Enemy Lines and Zimbabwe respectively. An early adventure for him was sweet-talking his way into becoming a crew member on a yacht that was participating in the Whitbread Round the World Race, a sailing competition that found the seasick-prone Deakins circumnavigating the world. It was an experience that resonates with him to this day.

As someone with an affinity for war movies and documentaries, Deakins’ earliest forays into filmmaking found him hired to head into war zones in Eritrea and what was-then Rhodesia in the ‘70s to shoot what became Eritrea-Behind Enemy Lines and Zimbabwe respectively. An early adventure for him was sweet-talking his way into becoming a crew member on a yacht that was participating in the Whitbread Round the World Race, a sailing competition that found the seasick-prone Deakins circumnavigating the world. It was an experience that resonates with him to this day.

“It was one of those opportunities I couldn’t turn down,” Deakins said. “I didn’t have any responsibilities. I was starting to get some work in London shooting documentaries and I heard about this job coming up with this television company. I went on this interview and pretended that because I was brought up in Devon that I was a very experienced sailor. But I wasn’t at all. I’d been on a dinghy. But I got the job. I had to learn to sail to become a member of the crew and spent nine months on the yacht. I was part of the crew but I was also making a film at the same time. It’s tough being on a yacht with nine or 10 people and not having a way to get off. I’m not good with people. My biggest takeaway was the life experience really. It’s something where some image of that comes into my mind every couple of days. I think that was the great thing for me about shooting documentaries. I got to experience different parts of the world that I wouldn’t have any other way. Back then, not many people had sailed around the world. Now they seem to. Back then it was quite an event really.”

Throughout the ‘80s, Deakins worked on music-related projects ranging from short-form videos to full-length projects like Ray Davies’ 1984 effort Return to Waterloo. Other full-length projects he lent his talents to were Alex Cox’s 1986 biopic Sid and Nancy, the 1987 British Terry Jones comedy Personal Services and the 1990 Mel Gibson/Robert Downey, Jr. buddy comedy Air America. By 1991, Deakins was ready to walk away from Hollywood until a chance 1991 meeting with the Coen brothers, who sought him out, changed his mind. The English cinematographer met his future wife shortly thereafter.

Throughout the ‘80s, Deakins worked on music-related projects ranging from short-form videos to full-length projects like Ray Davies’ 1984 effort Return to Waterloo. Other full-length projects he lent his talents to were Alex Cox’s 1986 biopic Sid and Nancy, the 1987 British Terry Jones comedy Personal Services and the 1990 Mel Gibson/Robert Downey, Jr. buddy comedy Air America. By 1991, Deakins was ready to walk away from Hollywood until a chance 1991 meeting with the Coen brothers, who sought him out, changed his mind. The English cinematographer met his future wife shortly thereafter.

“I’d actually given up the film business,” he said. “I’d done a lot of films by then and my agent called up and said these guys the Coen brothers wanted to meet up with me. It was just out of the blue really. I met up with them here in London and we just got on. James and I met on a film called Thunderheart in while filming on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. It wasn’t a bad movie. It was a great subtext and a very interesting film to do. What made it even more so was that James was scripting and I was shooting. We found we both had recently moved to Los Angeles and we were basically living in Los Angeles a few hundred yards apart. It was pure coincidence so it seemed destined.”

Fast forward to 2023 and Team Deakins is thriving with their podcast while indulging in the duo’s love of cinema. The twosome have wrangled a number of notable names including actors John Turturro and Frances McDormand, composer Carter Burwell and director Neil Jordan.

“It’s really great talking to these people, some of which we’ve never met before,” Ellis said. “We never met Neil Jordan before, but we admire him, so that’s been great. Also, we do all this homework so we see the films that they’ve done but we try to focus on early films and films that aren’t as well-known as well. We’ve found some incredible gems of movies we never even heard of.”

Deakins added, “Like James said, we got to talk to some of my complete idols like Alex Webb, the stills photographer and Harry Gruyaert, another great stills photographer. We also talked with Andrey Zvyagintsev, a Russian director who now lives in Paris and who did Loveless and Leviathan.”

Being the cinephile that he is. Roger Deakins was more than happy to share some of his favorite films.

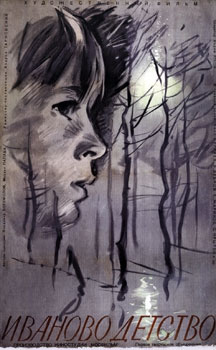

Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

“This is Andrei Tarkovsky’s first movie. I could say any one of his movies because he’s a film genius. I went with Ivan’s Childhood because it’s a comment on a real war and a comment on a child that lost in this world that he doesn’t understand. I connected with it. But I could have said any of Tarkovsky’s films like Solaris or Stalker.”

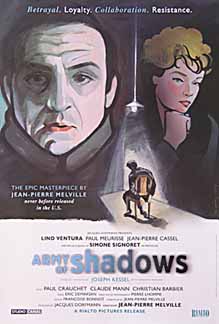

Army of Shadows (1969)

Army of Shadows (1969)

“The second movie would have to be Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows. Again, it’s a war film that takes place during the Second World War and is about the French Resistance. I suppose when I grew up, I spent most of my childhood listening to may dad tell me about his war experience. And my dad had this very interesting war, so I guess this might have stayed with me. I’m really into war stories.”

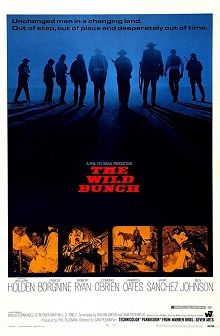

The Wild Bunch (1969)

The Wild Bunch (1969)

“I could also say Come and See, which is also about the Second World War. But I think I’d have to say The Wild Bunch, which in a way is about war. It’s an allegory about Vietnam in many ways I suppose. I also connected with it because it’s about a world that’s changing. And even those these characters are outlaws, they live by a code. Even though the whole world is changing, they don’t understand it. Wars are being fought with Gatling guns, machines and weapons they don’t understand. I feel like it happens to every generation and I certainly am aware of it now. I think [Sam Peckinpah] was aware of it then, which was the ‘60s. Some people loved it for its violence and Peckinpah was really upset about that, because he was just trying to show what violence was really like. You would open the Sunday paper in England and there would be a double-page spread of some Don McCullin image from Vietnam of death. That’s weird. I think Peckinpah gave violence a reality that was different.”

Roger Deakins will be appearing on May 17 at the 92nd Street Y, 1395 Lexington Ave., NYC. For more information, visit www.92ny.org or call 212-415-5500.