In a lesson that would inform his life’s work, Robert Caro’s editor at 1960s-era Newsday implored the author of The Power Broker and Master of the Senate to, “Turn every page.”

(Photo by Don Pollard)

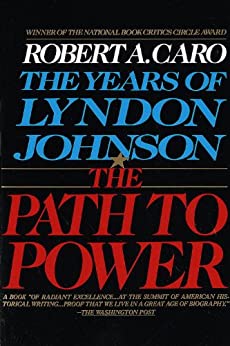

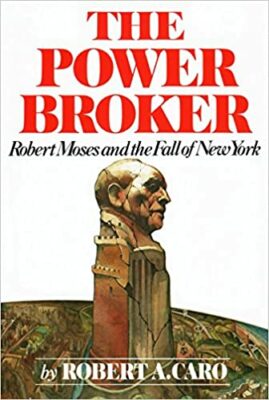

That investigative-reporting imperative, shorthand for leaving no research stone unturned when working on a story, would go on to fill the pages of Caro’s definitive texts for decades to come — from his Pulitzer Prize-winning first book on iconoclastic urban planner Robert Moses to his, perhaps, final book on President Lyndon Baines Johnson that impatient Caro fans await. For Caro, his biographies must bring novelesque character-study nuance and prose, and a visceral sense-of-place, to his non-fiction works.

(Photo by Don Pollard)

He must know how the book will end before he can begin it, and he must dive deep into the archival papers of his subjects, turning nearly every page, to get the business of book writing done, Caro said in a conversation on craft with writer Brenda Wineapple at the New York Historical Society last month.

Turning every page in archival research rooms is where ‘I felt at home’

It was editor Alan Hathaway’s directive to turn every page, which is also the name of the Oscar-nominated documentary on Caro and his longtime book editor Robert Gottlieb, that led Caro to his spiritual work home: The nation’s archival research rooms and libraries, which preserve historical and cultural memory and transport him to the past. On Caro’s first trip to the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Texas, standing amid thousands of boxes filled with the official Lyndon Johnson Papers, “I felt at home,” he said. “I was moved.”

Caro would go on to spend days, weeks, years and decades in such archival spaces, combing through boxes and file folders packed with letters, memos, reports, speeches and more. “Sometimes the whole day would go by,” he told Wineapple, “and I hadn’t even thought about it.”

Stoking the reader’s imagination: ‘The writing has to be at the same level as a work of fiction’

“If the work is to endure,” Caro said, “the writing has to be at the same level as a work of fiction.”

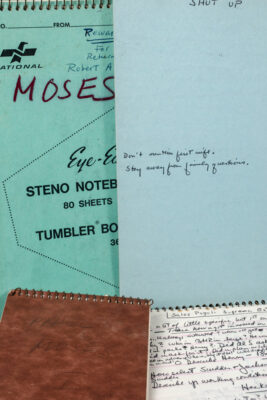

(Photo courtesy of Robert A. Caro Archive, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New York Historical Society)

To do just that, Caro is famous for going to absurd lengths to immerse himself in the places his real-life characters lived, in the moments they lived them. In a now well-known story, Caro’s Native New Yorker-shaped sensibilities couldn’t grasp the essence of LBJ’s Texas Hill Country roots via random visits to the former president’s home turf. So he and wife Ina, Caro’s sole researcher, packed up and moved there for three years to soak up the people (and earn their confidence) and the places that shaped LBJ’s experiences, sensibilities, and what motivated him.

It’s how he got to know LBJ’s milieu, a remote part of the country where one could drive 20 miles and not spot a single house, Caro said. And it’s where time spent with LBJ’s brother Sam, seated at the dinner table in the Johnsons’ old family home in Johnson City, TX, Caro managed to disarm the brother’s bravado. At that table, awash in a trance-like fog of memory, Sam revealed scenes of the acidic father-son dynamic he’d witness, until then unknown, that in part shaped his brother and informed LBJ’s path to power, Caro said.

It’s how he got to know LBJ’s milieu, a remote part of the country where one could drive 20 miles and not spot a single house, Caro said. And it’s where time spent with LBJ’s brother Sam, seated at the dinner table in the Johnsons’ old family home in Johnson City, TX, Caro managed to disarm the brother’s bravado. At that table, awash in a trance-like fog of memory, Sam revealed scenes of the acidic father-son dynamic he’d witness, until then unknown, that in part shaped his brother and informed LBJ’s path to power, Caro said.

It was necessary to live in these places among these people, because “if I didn’t understand them, I didn’t understand LBJ,” Caro said. “You have to make the reader see the scene.”

Knowing how it will end before you can begin

For Caro, the final line of his books shapes the entire narrative that precedes it. “I have to know the last sentence before I can start the book,” he said.

(Photo courtesy of Robert A. Caro Archive, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New York Historical Society)

When working on The Power Broker, which is as much a biography on Robert Moses as it is arguably the seminal political and cultural history of 20th century New York City, Moses stumbled on a scene that would fill the final pages of the 1,000-plus page book. At the end of the book, Moses, now an old man, rails against the “ingratitude of the public,” Caro said. In that moment, “I knew the last line, and I outlined the book from beginning to end.”

Indeed, as the entire theme of The Power Broker came into view, the final scene echoes one that opens the book when Moses is a young man on the Yale swim team. In both scenes, Moses serves up the petulant arrogance that helped one powerful man leave the most indelible imprint on New York City’s urban landscape than any single person before him. Caro has used that last-line method ever since. “I have to know what I’m writing toward,” he said.

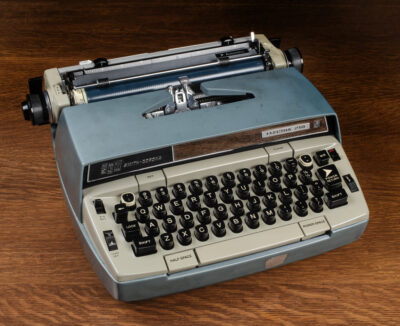

And as Hemingway said, when you wrap up a day at the computer, or in Caro’s case, the typewriter, “always stop when you know what the next sentence is,” he said. “This way the next day you won’t start with a blank page.”

And as Hemingway said, when you wrap up a day at the computer, or in Caro’s case, the typewriter, “always stop when you know what the next sentence is,” he said. “This way the next day you won’t start with a blank page.”