Part III: exploring contemporary law, business, and education

In our last installment of Long Island Cannabis Conversations, we discussed the legal principles and challenges involved in the Shinnecock Nation’s cannabis start-up in Southampton, and how embracing cannabis as a medicinal and recreational resource doesn’t always happen overnight.

For this installment of the series, we’ll zoom out our lens to look at the state of recreational cannabis rollout across Long Island as well as in New York City and State, with an eye toward breaking down the laws, business realities, and educational opportunities in our area.

Slowly but surely, cannabis programs and courses have been popping up in New York colleges and universities, including institutions such as Farmingdale State College, Queens College, Medgar Evers College, Niagara Community College, Cornell University, Nassau Community College, and Hofstra University.

These offerings range from online courses and cultivation certificate programs to cannabis business and legal classes. As a result, students and early-career professionals around the state are getting clued into what is likely to be one of the largest tangible industries, if not the largest, in New York State in coming years.

At the same time, Long Island communities have almost entirely opted out of New York State’s recreational cannabis program, meaning that local access for both adult-use (a.k.a. recreational, or retail) and medicinal users may soon rely on delivery or pick-ups from other areas, and that tax revenues will also end up outside of Nassau County municipalities.

To help make sense of the current landscape as well as the road ahead, Anton Media Group recently checked in with Andrew Cooper, Esq., LLM, Chair of the Cannabis & Psychedelics Practice Group at the law firm Falcon Rappaport & Berkman LLP, a board member of the JUSTÜS Foundation, and an Adjunct Professor of Law at the Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University. Cooper holds both a Bachelor of Business Administration and a Juris Doctor degree from Hofstra, where he served as Business Administrator of the Hofstra Law Review (and where, his LinkedIn reveals, he also played rugby), alongside a Master of Laws from New York University.

Cooper is currently teaching a course at Hofstra Law entitled “The Law and Business of Marijuana.”

The aerial view from Long Island

“Here’s why I’m not overly critical of the Office of Cannabis Management (OCM): when I compare New York State’s legal cannabis program to other states, I think New York is making a way bigger effort to truly have a market emerge in a socially equitable yet fiscally responsible fashion.”

“Let’s compare that, for example, to New Jersey, which has tasked its registered medicinal operators with doing that. The state said, ‘Here, we’ll let you guys build the recreational market: seven of them operating in the state, with thirteen locations, and as long as you can show us that we can still service your medical market, then we’ll let you do it. But if you don’t, we’ll fine you thousands of dollars a day.’”

“We found out that the same day they opened, in April 2021, they were already violating the state’s rules. They were selling adult-use products during hours that were segregated from medical use, and they were taking the fines. Now we found out, in early April this year, two pre-existing medical operators were restricting the number of point of sale (POS) systems, the number of registers, that could be used for medical, during overlapping times.”

“Average wait time for adult use? Under five minutes. Average wait time for medical? That was 17 to 30 minutes. Again, they were fined, and they don’t care.”

“Also in New Jersey, their law let every municipality opt out of every license type. It’s not really that big a deal, because you’re not going to be heavy on the processing side in suburban areas, but when you let every town opt out of every license, all kinds of operators are going to be having a hard time finding spaces.”

“They rolled out a program where you can apply for a conditional license, where you apply first and then find the space to operate, or an annual license. Most people opt for conditional, because there’s no site control, to find a site and then convert to annual. They have hundreds of licenses in New Jersey that are conditional, and a handful that have concerted to annual.”

“Until you convert to annual, you can’t even start your construction. At best, by Q4, we’re only going to have a handful of operational retail locations in New Jersey. And even though people say, ‘Look at the sales,’ it’s on the backs of out-of-state, multi-state operators with no connection to New Jersey and no social equity foundation.”

“In New York, yes, we don’t have a lot of open locations, but here’s what we do have: as many open retail locations as they have annual licenses in the social equity marketplace.”

“So let’s compare apples to apples: if you look at their recent, newly minted licensees, we’re pretty close. I’ll take New York’s roll-out over that.”

Facing today’s cannabis sub-market

“There have been hiccups, yes. We didn’t accommodate this ‘sub-market,’ and I think we created a demon.”

“When the Marihuana Regulation and Taxation Act (MRTA) was passed, there was language that says that you can’t sell, and people took that to mean, ‘Well, we can give away.’ Whether they were brick and mortar, or kiosks. or carts, or in a park, they were building on a concept of gifting: ‘We can sell you a CD, and give you the cannabis.’”

“A year ago, just about now, there were perhaps 12 or 15 operators out there (not including black market legacy operators, of course) in the open who were using the concept of gifting. That turned into setting up clubs, where you pay for membership and get the cannabis. Suddenly we have 30. Then people decided they’d start selling out of existing bodegas. When some people saw none of those things having to deal with enforcement, they thought, ‘Well, maybe we’ll open up a brick-and-mortar store.’”

“The proliferation of that market came from truly nowhere, because people in that marketplace are not historically operators and are simply opportunistic, and said to themselves, ‘Maybe it’s okay.’”

“Now we have tourists thinking all these stores are legal and regulated, and around 1700 of nonlicensed stores in the state.”

“The biggest challenge we have toward having a truly fiscally responsible, robust, socially equitable market is to try to minimize the unregulated component by either reducing that market or giving those operators a path to becoming regulated, and licensed.”

Financing and real estate meet red tape

“The second big challenge we’re now having in New York has been around funding for Conditional Adult Use Retail Dispensary (CAURD) social equity licensees, some of whom opted out of the state’s [so far only partly endowed] social equity fund because they didn’t want to wait. If you can’t use the fund, and you can’t give up control to an equity partner by law, then you’re fostering an environment that almost forces them to do backdoor agreements to be able to build.”

“The other part is this, and it’s more challenging: landlords who may want to participate in cannabis may be prevented from doing so because of their mortgage documents. The tradiitonal mortgage documents say that any illegal activity is a condition of default, so they may want to do it but they have to get permission from their lender. If their lender is among 95 percent of lenders in the country, they’re going to say no.”

“It’s even a challenge to get it approved by a lender who may have a cannabis compliance program, like Valley Bank, or DIME. Credit unions are most likely, because they’re more likely to develop compliant cannabis programs.”

“Suffolk Credit Union just got into the cannabis space. They just rolled out a program, and that’s going to solve a big part of the problem locally.”

“Valley doesn’t seem too interested in getting involved with smarter operators, and remember, banks are on a federal, state, or county charter. The banks that do work with cannabis mostly do so as depositories, not lenders.”

“The third problem we’ve found is that, in large municipalities that are all-in for the program, like New York City, operators are having trouble finding locations because of the rule that says retailers must not only be hundreds of feet away from houses of worship of schools, but also 1000 feet from other cannabis retailers. Personally, I don’t think businesses are going to win or lose because they’re 1000 feet from the next guy; I think they’re going to win because they’re cultivating a brand around things that are important to people.”

“The problem gets worse when you get into more rural areas like Long Island. On Long Island, four towns didn’t opt out; one of those towns is next door to the Shinnecock Nation, and you’re not really going to be able to compete with their prices, so that really leaves three towns, Babylon, Brookhaven, and Riverhead, and the available space gets really small when you’re talking about 23 CAURD licenses on the island. There’s no cap on the number that can be issued, though.”

“If one town or city opts back in, and there are rumors, it does create more room, and the numbers would probably work a lot better than they do currently.”

“Meanwhile, CAURD licensees who opted out of the social equity fund are having to compete for locations with people who chose to participate in the fund, whose locations are being negotiated by a broker for the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York (DASNY).”

“What we have now is a race to the site.”

“On Long Island, the rule is a 2000 square-foot radius between sites, not 1000, since it’s based on population density. As a result, there are fewer prime sites. That’s the most recent challenge, that we’ve been having in the past few weeks.”

“I’m still 100 percent behind New York. For me, I start with the intention of regulations. I think these things that happened were regrettably unseeable, so the question is what happens next.”

On teaching cannabis, law, or anything else

“They key to learning is having fun learning.”

“That applies to everything. People don’t understand, and I used to tell kids when I would coach any sport — soccer, lacrosse, hockey — that the only way you’re really going to be successful is if you’re enjoying yourself. As you realize you’re getting better you’ll keep wanting to do it, and then there’s a cycle happening.”

“If people don’t feel like they’re working, they just seem better able to process information.”

“I try to teach in a non-traditional way. I digress a lot, and use a lot of anecdotal evidence, because I don’t like to wait to the end to be critical. And I appreciate that students don’t feel like they’re being thrown information and being asked to remember it; they remember it like I do, by connecting it to people or events. That’s how I remember names now, and it’s changed everything.”

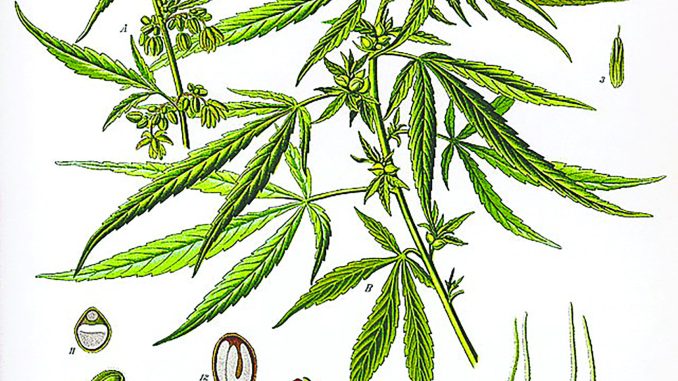

“We were built on such a foundation of agriculture here on Long Island, and on hemp agriculture (remember, it’s the same plant), though it was really only being used medicinally and industrially.”

“Historically accurate, scientifically accurate information is something that’s going to get people to the point where they’re thinking, does this law, or this opt-out, make sense for us? Because we can limit it, we can tax it, why not? But if you’re worried about it, let’s talk about why, and give people the chance the let their guards down by making the connection historically.”

“I think it’s a matter of educating communities on Long Island, and other places in the state, about the value and incentives of opting back in: remember, that’s not just real tax dollars, but also community give-backs that applicants are asked to describe in their applications, how they’re going to create jobs, support schools, or something else, to become an important part of the community.”

“Places like Long Beach, with millions in budget deficit, can realize that while they can’t make that up through taxes, because people won’t stand for it, they do have a solution: cannabis.”