Joe Pepitone, the Brooklyn-born New York Yankee All Star, was the team’s link from its championship run in the early 1960s to its agonizing dry period in the mid-and-late 1960s to the rebuilding process that resulted in more titles in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Pepitone, who died last month at age 82, was born to be a Yankee. He was a lefty slugger from the sandlots of Brooklyn with a swing tailor-made for Yankee Stadium’s short right field porch. At Brooklyn’s Manual Training High School, Pepi was being touted as a possible $100,000 bonus baby signee. In the Fifties, New York public schools were already deep into their Blackboard Jungle phase. Zip guns were all the craze among feral youth. One day, one of Pepitone’s classmates was showing off his newly constructed piece. The boy actually stuck the gun in the 17-year-old Pepitone’s stomach—and pulled the trigger. The teenager survived. However, his value as a ballplayer went down markedly. He ended up signing with the Bombers for $20,000. Something else happened. Three days after the shooting, Pepitone’s father, then only 39, died of a heart attack.

Pepitone didn’t disappoint. After several years in the minors, the husky first baseman was ready for the big leagues. Pepitone played part time for the 1962 World Championship team. The Yankee front office thought so highly of Pepitone that they were willing to trade veteran first baseman Bill Skowron to the Los Angeles Dodgers to make room for Pepi.

It worked. Pepitone was popular with fans and teammates alike. He was productive too, belting 27 home runs, while driving in 89 runs in 1963 and 28 home runs and a career-high 100 runs batted in 1964. The Bombers kept winning, taking the American League flag in the 1962, 1963, and 1964, while snagging the 1962 World Series in a heart-stopping 1-0 seventh game win over the San Francisco Giants.

Pepitone at first, along with Bobby Richardson at second, Clete Boyer at third and Tony Kubek at shortstop formed the Yanks’ Million Dollar infield, a name inspired by the Million Dollar Movie highly popular among New York viewers in those pre-cable television days.

Pepitone was also part of a new breed of athletes that began to emerge in the mid-1960s: Hipsters who sported long hair, while wearing expensive threads, questioning authority (including their coaches), and performing with a certain flair on the field. Pepitone was no Muhammad Ali or Joe Namath. He did make a name for himself by introducing blow driers into locker rooms. No greasy kid stuff—and no Brylcreem, either.

The man had a troubled life. After losing the 1964 World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games, Yankee management panicked, firing first year manager Yogi Berra, a short-sighted move that haunted the franchise for years. (When the Yanks did win the American flag in 1976, skipper Billy Martin had brought back Yogi as a bench coach.) Overnight, the Yankees grew old. Richardson, Kubek, and Whitey Ford retired. Boyer, Roger Maris, and Elston Howard were traded. After the 1966 season, Mickey Mantle was moved to first base. An unhappy Pepitone was transferred to centerfield. The man didn’t care for the moves, but he was the team’s most productive player in those nightmare years when it all seemed to be coming apart: The South Bronx neighborhood, New York City, and the country itself.

Pepitone was a good soldier. By 1969, the great Mantle had retired, itself a liberating experience. The Yanks could now begin anew. That year, Pepitone played with Bobby Murcer, Roy White and Thurman Munson, young stars who would lead the team to winning records in the early 1970s, themselves a prelude to the championship run of 1976 to 1981.

In 1969, Pepitone was traded to the Houston Astros for Curt Blefary, another lefty hitter who was also a native New Yorker. Blefary didn’t work out. But the trade set certain wheels in motion. Danny Cater was the Yanks’ first baseman in both 1970 and 1971. After a subpar ’71, Cater was traded to Boston for ace reliever Sparky Lyle. That was the pivotal deal that sent the Bombers on the path to late 1970s glory.

Pepitone played for Houston, the Chicago Cubs, and the Atlanta Braves before ending his career with a stint with the Yakult Atoms in Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball’s Central League.

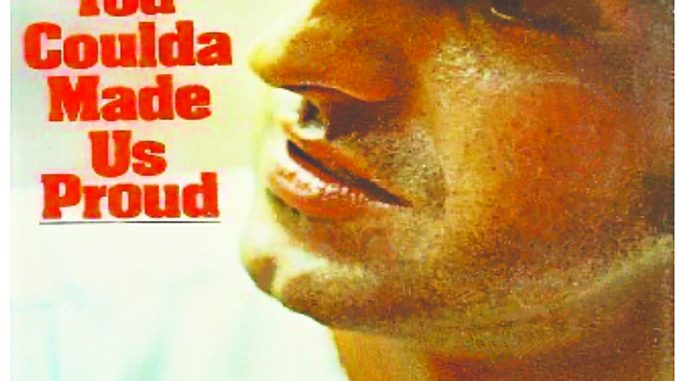

In his 1975 mournful and brutally honest autobiography, Joe You Coulda Made Us Proud, the man recalled an exchange with his grandfather. The crusty old timer gave his grandson a five-dollar bill. “Congratulations,” the old man said (as best can recall). “Take this money, go to the butcher, buy some brains and put them in your head.”

What? This then-teenage reader thought. No shame in the Japan Leagues. Numerous major leagues have made that same trek once their time in the American big leagues comes to an end. Alas, Pepitone spent less than a year in Japan.

Out of baseball, Pepitone struggled. He suffered several brush-ups with the law, being arrested for drug possession and even spending time at New York’s notorious Riker’s Island. A 2018 profile on Pepitone in New York magazine revealed a man still suffering emotional scars from that long-ago incident at Manual High School. Pepi recalled that a physician told him: “A fraction of an inch either way, you would have been dead.” “To this day, I don’t like talking about it, because it brings back really bad memories,” he told New York. “As I say, I was 17 years old.”

Joe Pepitone was a Yankee. And a proud one. Always popular, too. Yankee fans remained forever grateful for the way he carried the banner of Yankee pride in those dark days of the late 1960s. He later served as a Yankees’ coach. He received moving ovations at annual Old Timers Day events, themselves the final of rite of passage for any Yankee great.

It was the fans way of saying: Joe Pep, you always made us proud.