While it’s hard to imagine now, hunting whales has been practiced for millennia. Native Americans on Long Island utilized stranded whales to feed whole communities. The Basque region of Spain was the first to establish a commercial whaling practice, and they dominated the industry for more than five centuries. Commercial whaling in North America began almost as soon as the continent was colonized. Sag Harbor was the principle whaling port, and actually grew to be one of the most productive in the world before fire devastated the town.

Products derived from whales included corsets, combs, oil for lamps and machines, wax for candles, cosmetics, and even margarine. High demand meant that the industry was always in need of capable people to man the ships. This included people from all races, often in high numbers.

Historical Society.

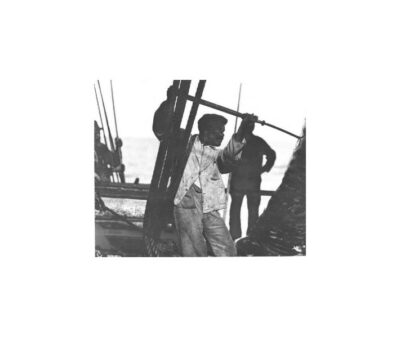

(Photos by Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum)

Estimates put the number of people of color employed on whaling crews between one quarter and one third. It was the first integrated industry and one that allowed people to advance based on their abilities. In fact, it was common for people escaping slavery to use the sea as their means of reaching a free state. Nomi Dayan, executive director of the Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum, sheds some light on how African-American whalers found agency and freedom doing this dangerous work. “Whaling employed the most diversified workforce, among other occupations at the time. So the question is, why would whalers of color endure hard work and awful living conditions, sometimes poor pay and serious danger with every whale hunt? They chose to work at sea because their options on land were limited, and for some this was a way to autonomy.”

(Photos by Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum)

The first black Americans to be treated as citizens were sailors during the 19th century. Because the US feared that the British would capture their sailors, they gave them something called a seaman’s protection certificate. It was an early version of a passport. American sailors carried this document as proof of citizenship. So for black mariners, there was nothing else like this at the time. And so this was very important for African Americans before they were officially defined as citizens. People used these documents as proof that they were sailors in order to escape slavery.

Many of the whaling captains and ship owners were Quaker. Tolerance is one of the core tenants of the Quaker belief, making them open to hiring people of all races, including African Americans. The other side of this practice is their need for plentiful, cheap labor. “So it was a marriage of this ideal and this need African Americans also who were escaping slavery, but quickly disappear on the waterfront… especially for people in maritime trades, in a few days you could disappear.” Dayan said.

In whaling there was opportunity for people facing work discrimination on land and people escaping slavery. On the other hand, Black whalers faced racial barriers to advancement. People of the same rank were paid the same, regardless of their race. They also slept in the same quarters and ate the same food. This meant that all greenhands, whatever their ethnicity, were housed together, performed the same duties, and ate the same quality of food. That being said, agents did tend to lump black whalers into service-based positions. According to Dayan, “agents often would make a decision based on how someone looked into what kind of job they would be cast for. So the majority of black seamen worked as green hands, a low rank on the ship, or just a general seaman. Some were cooks and stewards, which paid a little bit better but didn’t necessarily build a career. Some whalers of color did become mates. It was very rare for an African American whaler to become Captain.”

There are examples of Captains of color, such as William T. Shorey on the West coast in the waning days of whaling. He was often called the Black Ahab, after the character in Moby Dick. Probably the most famous local whaler is Pyrrhus Concer of Southampton. He was born about 1814. His mother was enslaved and he was sold as a slave at the age of five for $25. In his late teens he became a whaler and willing to greatly improve his economic situation. He also inherited some land, which he was able to maintain for the rest of his life. Some of the artifacts from his home are on display in the museum.

(Photo by Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum)

Because of the inherent nature of life on a ship, it was essential for whalers to get along. People lived in close quarters aboard ship. Each person had a duty to perform, and all of those jobs had to fit together in order for things to run smoothly. “For the most part, it was in everyone’s interest to work together in a collegial, friendly manner, because the more whales you caught in the shortest amount of time, the sooner you were going to go home and the faster you were going to get paid. The majority of whaling voyages went without conflict; people kept personal tensions and prejudices check.”

There are some records of tense interactions, but these seem to be resolved fairly quickly. In one instance, a crewmember used a racial slur aboard ship and was flogged for it. Another wrote in his diary that he was surprised to see a ‘colored man’ giving orders. These individuals had some personal conflicts, but after surviving a severe storm, they came out with more respect for each other. Dayan confirmed that “the majority of whale ships sailed with everyone wanting to work together and get the job done. Everyone’s profit depended on it, but there are examples of how your race did influence how shipmates interacted.”

Studying the racial identities of whalers can be difficult, primarily because ship’s records did not make note of an individual’s race. Even the census records of this time kept track of those demographics, so it is sometimes possible to trace a whaler’s background that way. Dayan pointed out that many whaling ships simply recorded the person’s date of birth and appearance. “you’d have your place of birth, some noted your skin color and your hair type. So that’s often a first clue researchers look for: dark. (Their) hair could be curly or dark. Often we do find it’s not completely reliable because it was up to the person’s personal discretion. Often one whaler would be listed as dark on one voyage, tan on another. So it’s a clue but you can’t trust it.”

From Sea to Shining Sea: Whalers of the African Diaspora Special Exhibition will run at Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum through 2024. The Museum is located at 301 Main Street, Cold Spring Harbor.