What can ancient wisdom teach us about today’s crises?

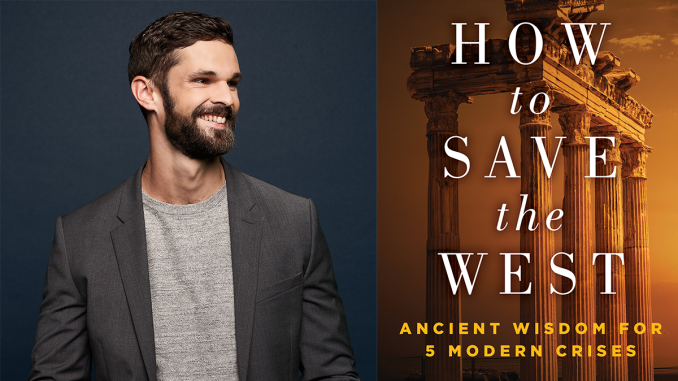

According to Spencer Klavan, author of “How to Save the West: Ancient Wisdom for 5 Modern Crises,” it can teach us a lot.

“Whenever you call a book something like ‘How to Save the West,’ you have a certain imposter syndrome, or it’s impossible not to feel a kind of trepidation, but that’s actually why I wrote the book in a certain sense, that feeling of just overwhelm and despair that I think we all can relate to,” Klavan, associate editor at the Claremont Institute, says on today’s podcast.

Klavan adds:

What’s the role of a human being? What’s our place in the universe? What is good and what is evil? Those sorts of questions actually are human-sized.

And so I wanted to give people just a taste of some of the wisdom that we can get if we access these great texts and incorporate their wisdom into our lives, because we think of these things as kind of inaccessible or beyond us, but actually they’re there for you, and the book is designed to equip you with some of that.

Klavan joins “The Daily Signal Podcast” to discuss his new book, what he thinks the West needs to be saved from, and what he views as the biggest threat to the West.

Listen to the podcast below or read the lightly edited transcript:

Samantha Aschieris: Joining today’s podcast is Spencer Klavan. He is an associate editor at the Claremont Institute and he’s also the author of a newly released book “How to Save the West: Ancient Wisdom for 5 Modern Crises.” Spencer, thanks so much for joining. It’s so great to speak with you again.

Spencer Klavan: It is a real pleasure. Thank you for having me, Samantha.

Aschieris: Of course. Now, Spencer, this is your first book and it is quite a big undertaking, right, “How to Save the West.” So first and foremost, what was your inspiration for the book?

Klavan: Yeah. Whenever you call a book something like “How to Save the West,” you have a certain imposter syndrome or it’s impossible not to feel a kind of trepidation, but that’s actually why I wrote the book in a certain sense, that feeling of just overwhelm and despair that I think we all can relate to.

Last time you and I talked, it was about my podcast “Young Heretics” and through that podcast I got to know so many wonderful people, just everyday folks that were connecting with the great works of the Western canon with classics like Aristotle and Plato, the Bible, patristic literature, all that wonderful tradition that comes down to us. And I heard from a lot of them, from so many of them, that there was just this sense of helplessness when they read the news. Every day you get barraged by story after story that seems to kind of forebode disaster.

It’s like today the economy seems to be falling apart. Tomorrow, the kids are going crazy, everybody seems to be trans. Everything seems to kind of threaten these vast structural problems. And I think the natural response to a lot of that is for people to say, “Well, what can I do? How can I contribute or help in this kind of moment of crisis?”

And typically, I think we ask ourselves that question like kind of as if we were [Florida Gov.] Ron DeSantis, like we think about what law could we write that would save the country or how are we going to, tomorrow, rearrange the state legislature to fix this problem? And that’s when that paralysis sets in because, in fact, we’re not Ron DeSantis. We have the vote, thank God, but we don’t control vast swaths of history and we’re not going to muscle the world into shape just by sheer force of will.

So I wanted to write a book for people about how they personally, regular folks in their individual daily lives and communities, can preserve these traditions that come down to us from Athens and Jerusalem.

And the wonderful thing about Western civilization, Western culture is that it actually doesn’t depend on getting the perfect outcome in the 2024 election or fixing all these massive structural problems that we don’t have personal control over. What it really depends on is … what Harry Jaffa called the rescuing of the individual human heart from the black knight of nihilism and despair.

These questions that we’re up against now in this tumultuous era are so fundamental. What’s the role of a human being? What’s our place in the universe? What is good and what is evil? Those sorts of questions actually are human-sized.

So I wanted to give people just a taste of some of the wisdom that we can get if we access these great texts and incorporate their wisdom into our lives because we think of these things as kind of inaccessible or beyond us, but actually, they’re there for you and the book is designed to equip you with some of that.

Aschieris: Yeah, absolutely. And I wanted to ask you just a follow-up with “How to Save the West.” What exactly do you see the West being saved from? Is it a person, is it an institution, multiple people? In your mind, where do you see the biggest threat to the West?

Klavan: Well, I think the forces that are at play are bigger than any one person or institution. I mean, the closest thing politically to what we’re up against is something like oligarchic decay, just this real breakdown in social relationship, social fabric, the way that these sort of power brokers that we don’t fully understand have taken control of so much of our public discourse and our politics.

But at an even deeper level than that, you start to ask, “Well, why is it that we can’t get along, that we can’t have civil conversations anymore in politics?” And I think the answer is because digital technology, the revolution that we’ve gone through in just the way that we communicate with one another and relate to the world, has deeply unsettled our sense of ourselves and has raised up all these fundamental questions that are actually quite ancient.

And that’s where those crises start to emerge because we’ve done a lot in the past several decades to kind of scrap the Western canon, to say it’s chauvinist or racist or evil to study these great works, and, “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Western civ has got to go.” But the problem with that is that when you come up against these problems that are raised in the digital era, you then find yourself with no footing, no resources, and none of those treasures to draw on.

So I outlined these five crises in the book. The crisis of reality: Is there objective truth? The crisis of the body: Should we all upload our consciousness to the cloud or become postgendered, or what have you, or is there something meaningful about our bodies? The crisis of meaning and religion: How can we know that anything is really worthwhile and is it possible to believe in the wake of the scientific revolution? And then, finally, the crisis of the regime: How do we proceed as Americans when the country seems to be in such bad shape?

And I think that all of those questions are raised by the digital revolution, but they point us back to those ancient texts that we supposedly were supposed to throw out because they’re backward and superstitious. And I kind of try to offer some of the resources that come from that tradition for people to try to answer those questions.

Aschieris: Yeah. I’m so glad you brought up these five crises because I have them written down here. I wanted to pick your brain about them. You talked about the crisis of religion, the regime crisis, the crisis of meeting, the body crisis, and the reality crisis. From your perspective, which do you think is playing the most significant role in today’s society? And is there a way to kind of counter that role, that influence that you think we’re seeing?

Klavan: Yeah, I think that the most urgent one of those crises that you listed is the body crisis. It’s expressed in so many different ways. Obviously, the rise, the sudden uptick in gender dysphoria and the rise of people talking about feeling uncomfortable in their bodies and their sex as male or female. That’s the most obvious one.

But you hear people saying all sorts of things that go even beyond that, into, “Well, we should become posthuman, should actually upload, we should put chips into our brains. We should be adding on digital appendages to ourselves until we just don’t really suffer the limitations of the human body anymore.”

And what I argue in the book is that’s actually a very, very ancient impulse. It goes back to the Neoplatonists and to these philosophers in Ancient Greece who just wanted to float up out of their flesh and be free in this kind of spiritual nether region essentially.

And what I suggest is that that kind of anxiety, that horror at the body, which is making itself felt in the digital age, is threatening to disconnect us from everything that makes us happy and fulfilled. That our joy, our virtues, our fulfillment are actually in our embodiment. They take place in this kind of union of body and soul, which makes us what we are.

And so what I propose in the book is something very simple to kind of move away from this, and that is to regain ownership over our actual embodied experience.

I think we’ve been taught to distrust and revise and wish away the evidence of our own senses. You say, “Well, do you have a source to show that actually beauty is beautiful and strength and health are good?” And the answer is, the source is in my own experience, is in my daily practice and getting up and going to the gym and eating three meals a day, and these kind of basic encounters with how it actually is working out for us.

How’s it actually working out for us, not just in some imagined utopia in the future, but in real life, in the here and now? How’s it working out for us to kind of upload all of our conversations to Zoom and just shut our schools down and do everything digitally? It’s actually not working very well, and the promise that someday it’s going to make us all happy and free is a very dubious one. So I would suggest that that’s where we kind of start, is reencountering the just hard and fast reality of embodiment in the here and now.

Aschieris: Yeah. And also, too, do you think that these different crises are intertwined, like, how do you see them playing out in the modern day, in society today? And how can people recognize if they are experiencing any of these crises that you address in the book?

Klavan: Yeah. Well, I definitely think they’re intertwined. I think that in some ways you could view them as five sides of the same five-sided coin, if you can picture that. But what binds them all together I think is underlying everything, this crisis of religion, this sense that maybe we can’t believe in a God anymore, in any sort of absolute truth, in any sort of higher power.

And one of the things I try to argue in the book is that once you see that people are searching for a higher power, are searching for a source of absolute meaning, then the answer to your second question is everywhere.

You can see everywhere how people are grasping for that, reaching out, the way that, for instance, in 2020, people started kneeling at Black Lives Matter rallies, started worshiping “The Science.” Right? And you had people like Dr. [Anthony] Fauci coming forth and saying, “I represent the science. I am this kind of embodiment of occult wisdom and knowledge.”

I think that once you see this, it’s everywhere. And that’s part of the point of book, is, you take each of these news stories that in isolation seems kind of incomprehensible and bizarre, the COVID pandemic or the Black Lives Matter riots, and you start to realize that actually these are expressions in a certain sense of this underlying need for confidence in absolute truth, in the existence of a true and false that doesn’t depend on just what anybody thinks or the consensus that we all reach, but is actually objective. And the need to recover that and the need to invest ourselves in something that has real meaning.

So yeah, I think that that’s kind of the underlying thread that binds all of these things together. And I think that it is also a way to understand and explain a lot of the things that are going on in our news and in our daily lives.

Aschieris: How long do you think it will take for society to combat these crises? Is it even a possibility to be able to have a counterpunch, so to speak, to go against these crises that you talk about?

Klavan: Well, the good news and the bad news is that we don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow. And I really do mean we don’t know. I mean that I’m not going to predict doom and gloom and despair and disaster to you, but I’m also not going to sit here and say that everything’s going to be great if we just follow the five prescriptions in my book. That’s not what I’m selling.

And I say kind of at the outset that I would be dishonest to promise to people that there is some surefire way for things to go well today, that in our lifetimes we’re going to see a revitalization of the West and a full-scale rescue of all the political programs that we want to see happen. It could be, but it very well might not be.

So one of the things that I try to do is to suggest the West as a tradition, as a great conversation, has endured way, way longer than even America, much though we may love America. I mean, it goes back to Athens and Jerusalem are the two sources of this tradition and the two pillars of this civilization. And throughout the history of that tradition, there have been great moments of civilizational success and really wonderful times. And then there have been times of collapse and disaster.

And this is really the theme of the fifth section, the crisis of the regime. That nations do rise and fall. And there is such a thing as decline and decay. And our republic, America’s republic, is unfortunately showing, I think, a lot of symptoms of the kinds of decay that republics go through, the investment of a lot of power in a very few, the kind of occult status of some of our self-anointed leaders. This is all kind of looking at least like a threat to the immediate endurance of our nation, which is not something to sniff at or wave away.

That’s a tragedy, that’s a serious problem. But one thing that we should understand, if only to stave off despair, is that many of the great achievements of Western civilization were made at exactly the moment when everything seemed bleakest.

And one example I always give is Cicero, Marcus Tullius Cicero, the great Roman statesman, who was one of the last great men of the Roman Republic and left behind this fabulous wealth of political philosophy in defense of republican government essentially.

And in the immediate term, in the here and now, Cicero failed quite terribly because he was a casualty of the new regime, which was the Roman Empire. And he could never have known that it would be many, many hundreds of years before a new republic rose to sort of dominate the Earth. But in point of fact, fast forward to the 1770s and in walks John Adams, the man who has been pouring over Cicero’s own speeches since he was a lad, and who stands up and makes his great speech in defense of the Declaration of Independence, sets this country on the road to its birth.

And so when you’re talking about that kind of timescale, when you’re looking at a tradition which endures through that many catastrophes, and when you understand that you yourself are an inheritor of that tradition, we don’t really have a right to despair. Despair is not really an option. What we have is a job, and that is to wake up every morning and to seek the good, the true, and the beautiful as we understand them insofar as possible, insofar as it’s within our grasp.

And after that, we really do have to leave the rest to God because otherwise, these are the sorts of things, those bigger questions—”When are things going to get better? Is America going to be OK for the next 50 years?”—those are outside of our control. What’s in our control is to carry that torch, to carry the light of this civilization forward for future generations.

Aschieris: Now, obviously, I don’t want to give away any spoilers for audience members who do want to buy your book, but if you could just lay out maybe one or two of the most significant takeaways that you hope people take from the book. Obviously, no spoilers, but yeah, your thoughts on this.

Klavan: Yeah. Well, I won’t reveal which characters die and how many cameos there are. No. Yeah, I’ll say two things.

First of all, one thing I really hope people take away is a sense of ownership over their inner life. This is something that we have been talked out of, the reality of things like goodness, right? Which can’t be mapped anywhere on a brain scan, which don’t boil down to atoms bouncing off one another, that don’t boil down to chemistry sets and meat sacks, that are actually what philosophers call qualia, the qualitative reality of life. Everything important lives there, our loves, our desires, our virtues, our fears, our memories. Right?

And in order to understand ourselves, not just as kind of consumers or as material beings that just move through space, but actually as human beings who seek virtue and who love the good, we have to recover a sense that our inner lives have real meaning and are not arbitrary just because they’re subjective.

We use the word “subjective” sometimes to mean like, “Oh, that’s just your opinion, man.” But actually, the inner life, the subjective encounter with the world is fundamentally a part of reality. And I think people, I hope, will come away from this book with a renewed sense that that’s true.

And then the other thing I’d like to give people ownership over is the tradition itself. I hear from people all the time who say these funny things to me, “I’m not that smart,” or, “I can’t read these big texts,” or something. And the minute somebody says that to me, I know I’m about to have a really interesting conversation because I’m about to talk to somebody that isn’t bound by whatever kind of pieties that the academy has instilled in its latest graduating class.

And what they really mean by that—when they say, “I’m not that smart,”—is, “I for some reason have been sold the idea that the barrier to entry is too high for works like Aristotle’s ‘Nicomachean Ethics’ or even direct interpretation of the Bible, let’s say, or Thomas Aquinas.”

And I am here to tell you that with effort and dedication and with a receptive mind, these books are actually for you. They have endured, not because they furnish material for Ph.D. thesis, but because they are some of the best things that have ever been thought or written or said about how to be good at being human. And I think we all innately have an urge to seek that virtue to do rightly and love justice.

But again, it’s something that we’ve been talked out of and we’ve been told these books are too complicated or they’re somehow evil and wrong and backward. And instead what we ought to be saying is, “No, these things are there for you. They were written in some sense with you in mind and they are the best guide still to the challenges we face, even in the wake of all our modern gurus and gadgets.”

Aschieris: Yeah. Spencer, thank you so much for joining us. Just before we go, can you tell our audience members where they can buy your book?

Klavan: Absolutely. I’d be delighted. Yeah. I hope people will go and check out howtosavethewestbook.com and you can also, of course, get it on Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at the website of my publisher, Regnery. And you can even just follow me on Twitter @SpencerKlavan and I’ll tweet links at you constantly. But yeah, wherever books are sold, really, and I hope people enjoy it.

Aschieris: Awesome. Spencer Klavan, thank you so much for joining us. And for everyone listening, make sure you check out the book “How to Save the West: Ancient Wisdom for 5 Modern Crises.” Spencer, thanks so much.

Klavan: Thank you. It’s been such a pleasure.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please emailletters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.