The Smithereens are among a small number of groups whose music transcends time. Their new release, The Lost Album, showcases the band at their prime, beautifully capturing their unique ability to incorporate a wide array of musical styles culled from a variety of genres and eras into songs that are instantly accessible and permanently memorable. Formed in 1980, the New Jersey quartet is celebrating its 42nd year and is as busy as ever. With 11 studio albums released between 1986 and 2011, the band earned its legion of devout fans through a near-constant touring schedule.

Theirs is a lasting legacy of musical integrity and innovation that survived even the death of founding member Pat DiNizio in 2017. Known for their infectious, cleverly crafted songs that could be “mean, sweet, joyful, or brooding,” in the words of bassist Mike Mesaros, The Smithereens’ latest offering represents not only a remarkable gift for their fans, but also an enticing welcome to new ones. For the band themselves—Mesaros, drummer Dennis Diken, and guitarist Jim Babjak—The Lost Album is nothing less than “emotional gold,” according to Mesaros.

A lengthy conversation with Jim Babjak a few days before the album’s Sept. 23 release yielded wonderful insight, reminisces and advice from a man who was there from the beginning, candid in his memories, and a refreshingly down-to-earth human being. With many exciting events looming on the band’s horizon, The Smithereens are decidedly not relegated to being “only a memory.”

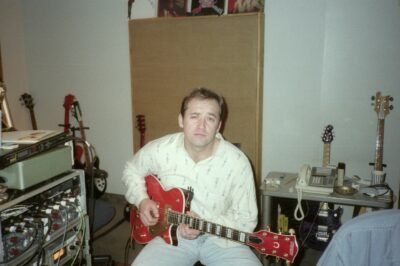

(Photo courtesy of Sunset Blvd. Records)

Discussing the background of The Lost Album and the decision to release it now, Babjak explained, “All I can say is that life just got in the way. There were just too many things going on. So, when we recorded that album, it was at a time when we lost our record deal and we just recorded everything that we had and wanted to see where we were going. When we got signed to RCA, we re-recorded half of them that made sense together. The rest of the songs that were left over, which is The Lost Album, were truly ‘lost.’ There’s such a mix of styles on this album, it’s almost strange releasing it as an album, but here’s the thing: When we were doing this, I was having a house being built, and we lost our record deal. I wasn’t sure what we were gonna do. But we are survivors so we just decided to go in and record it, but then after we got signed to RCA, we just kind of forgot about it and moved on to other albums, other tours.”

Babjack continued.

“I ended up getting a day job for 19 years. I was raising my kids and, you know, I guess since I’m not working my day job anymore and (after) the loss of Pat, we went back and started looking through our archives. When I discovered this, I thought, well, this is really good. I think our fans might like this! I think I did mention it to Pat maybe 10 years ago when I found it on a cassette, and (we) just never got around to it. You know what? There’s more stuff we have to look at, with what people might like. We don’t want to release everything. I also have a new album’s worth of solo material that’s all done and I never released it. It’s because of the day job, life going on, raising your family, making a living, touring; all this stuff just gets in the way, using all your tine to do this. It’s overwhelming, too. I’m in my record room right now and I’m looking at hundreds of cassettes. [Laughs] It’s crazy. At the same time, I’m working on new material for a new (Smithereens) album using Robin Wilson and Marshall Crenshaw, so there’s also that. You’ve got to keep moving.”

Babjak retains fond memories of the sessions for The Lost Album, though perhaps a bit blurred by time. “It was so long ago that I don’t remember if it was the first take or second take, but we did do the (basic) tracks first. Pat would normally sing a rough vocal, although the lyrics weren’t all done at the time. We’d be sitting around the table eating chicken parmigiana sandwiches and writing down lyrics! [Laughs] That’s the way it still works. I should say that; there’s no exact method.”

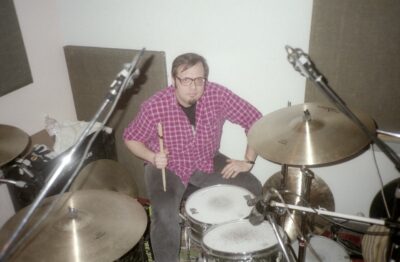

(Photo courtesy of Sunset Blvd. Records)

From a creative perspective, Babjak shared his views on his bandmates’ musical contributions. “Well, Dennis has been playing for a long time, and he can play anything. As you can tell by a song like ‘In a Lonely Place,’ he is just a great drummer who can fit in anywhere. His musical knowledge and his record collection … when I first met him, he had hundreds of records, and now it’s in the thousands. (He has) an encyclopedic knowledge of music.

Babjack also fondly recalled the common roots he and Mesaros share that date back to childhood.

“Mike and I both had accordion lessons when we were 7, 8, 9 years old, and we had our Communion together in 1964, so we go pretty far back. His training for playing bass probably came from the accordion or piano when you’re using your left hand to play bass notes and your right hand to play melody. I think Mike’s bass lines are so melodic. Dennis and I were playing years before we started and said, well, you can play the bass, because that’s the only instrument left! [Laughs] So he picked up the bass, I showed him how to play “No Matter What,” “Can’t Explain,” and “My Baby Left Me” by Elvis Presley. This was after high school when he started playing. He picked up a Rickenbacker bass at a flea market, and we both bought leather jackets there [Laughs]. He went away to college for a semester, came back, and he absorbed the (styles of) Dee-Dee Ramone, John Entwistle, Paul McCartney, Graham Maby—he absorbed all those styles into one! When he came back from college, it was like, holy crap, this guy’s a world class musician!”

When asked how Babjak and his bandmates manage to remain as grounded as they have, the former was matter-of-fact.

“I don’t know,” he admitted. “It’s hard for four guys to stay together that long. You know, the three of us went to school together—Mike, Dennis, and I—and we grew up in a working-class town, a factory town. U.S. Metals was there; my dad used to work there when I was little. Later on, he opened up a tavern. It was a blue-collar town, just a good work ethic. I don’t know—we all had (a lot) in common, we grew up in the same era, liked the same kind of music—which is very broad! During the disco period—not that I hate disco; it’s fine, I actually like some of it, but it’s not what I wanted to play—in those years I went back and bought records by Chuck Berry, Elvis, Buddy Holly, Fats Domino, Muddy Waters; I went back. We were all into the roots of what we were playing. That was my foundation; classic songwriting structure and a good hook and a good melody; we just all had this common interest and common goal to succeed as a band and make a mark.”

For the complete interview, please visit Island Zone Update.